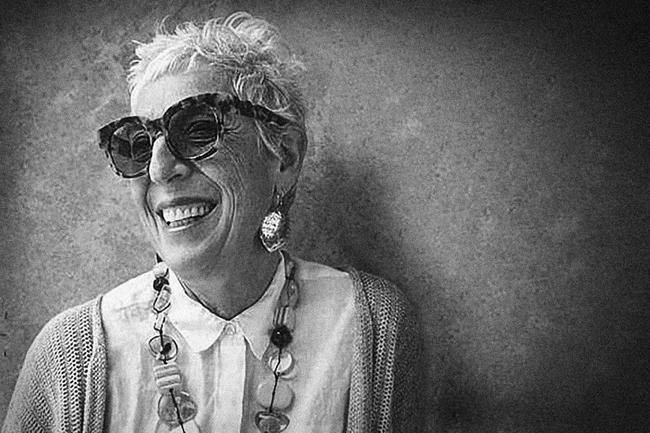

Conversation with Sophie Ebrard:

a lens on motherhood

Sophie Ebrard has had a good year. Not just commercially as a photographer and director but as a human being. Her deeply personal body of work, I Didn’t Want To Be a Mum, described as the truth about motherhood, is a project that has now struck a chord with so many more people than she possibly imagined.

Initially a self-exploration, it became a form of catharsis that addressed the realities of taking on an entirely new identity: becoming a mother.

Here we share a new short film of the show that captures the essence of what viewers experienced. The exhibition premiered in Amsterdam and Sophie now hopes to bring it to other parts of the world.

We talk to Sophie about all this and more, and about how she feels for the first time her role as a photographer goes beyond photography.

This is the first of a two-part interview series.

I love your honesty and decision to articulate your experiences of motherhood so openly and visually. It is a topic that resonates with many women but not many of us freely discuss.

When I became a mum, I was totally unprepared. It was pretty much a slap in the face. I was three years into being a photographer, I loved my life the way it was. I didn’t want children to disrupt the path I was on. I was determined that motherhood would not own me. I fought against its uncool image. I had just been shooting a series of images (that I would then become known for) on porn sets; how could I now push around a pram?

Once my son [Jules] was born, I loved him to bits but I didn’t love being a mother. I didn’t see myself as a mum. I felt sadness, I was mourning the old me. I was experiencing loss for the woman I had been and uncertainty for the one I could become. This in-between space left me feeling vulnerable and quite different from the brave, risk-taking, world-travelling, independent and professional woman I had been before giving birth. Suddenly I was a mum of this baby and felt an intense feeling of isolation. I also felt guilty for feeling all this. When a woman gives birth, society puts pressure on her saying it should be one of the most joyful moments of her life. But that famous rush of love doesn’t always come, and it certainly doesn’t always rush. The perception and reality of the day to day are so different it creates confusion, so women often struggle through this in isolation.

Tell us how you decided to create this body of work.

Through this project, by being so honest and raw about my own feelings, I wanted to start a dialogue free of shame, guilt and judgement. When my daughter, Louison, was born something really beautiful happened. I surrendered to motherhood and the idea of myself as a mum. But I also realised how difficult it had been when Jules was born, how much confusion and anxiety I had with my first child. I started to understand the conflicting emotions of motherhood.

So I started to research the subject and felt compelled to create this work. I began creating self-portraits of my daughter and I over the course of six months. I was also writing about all my emotions. And in my research I found there was a term for what I was experiencing and it was called matrescence.

I’m a mum of two kids older than yours and hadn’t heard of this word either until very recently. Microsoft Word doesn’t even recognise it in a spell check. Yet everyone knows the word adolescence, for example.

Matrescence is a term used by anthropologists to define the process and challenges of becoming a mother. We talk a lot about adolescence and how there is a transition (you have mood swings, your skin breaks out). Adolescence is the same terminology as matrescence. There are countless books written on the topic and everyone agrees it’s a transition.

It’s the same with matrescence but nobody actually talks about it.

It was really incredible for me to discover that term. It was a real aha moment and almost a validation of my feelings in the transition to motherhood.

We should start telling women that there will be an identity shift from the person she’s spent decades defining. That a transition period is entirely normal. That it won’t happen overnight. That there will almost always be a phase of mourning for the ‘old her’.

It’s incredible this topic is still a slight taboo today. In a culture focused mostly on the baby, we need to normalise that becoming a mother is one of the biggest changes a woman will ever experience in her life.

Women are often less guarded emotionally than men; we tend to confide more freely. But your own experience and the reactions to this exhibition show this is not always true. Any rite of passage in life takes time, of course; you are in that liminal space when you are in between what’s gone before and what’s ahead. And it’s full of bumps.

It took me five years to become a mother. I would say I might still be in the transition.

With most personal projects, photographers are telling some kind of story, there’s an emotional connection going on. But this project is so much more – it’s a kind of therapy, isn’t it?

Yes, absolutely. At first, it was really just about me wanting to analyse more deeply what I’d been going through. It was a sort of therapy. I wanted to get it out of my system. Doing this body of work was, for me, a way to heal and to process and understand what had happened.

Before the [exhibition] opening, I had no idea how people would react. It was such a personal part of my life and I had felt so alone in my experience. In an article published in Dazed before the opening I said: ‘If I can help one person to come to terms with her feelings and start a conversation, then I will be happy.’ We ended up having to buy tissues halfway through the week, because visitors were literally moved to tears. Parents, non-parents, women, men. The reaction was extraordinary. I was surprised and moved myself.

So many women came to see me and told me it’s exactly how they felt and thanked me for sharing this experience, and these words, and told me how much it was helping them. And, for the first time, I realised I am not alone in feeling this way; in having such conflicting emotions. If women knew that most people found it hard, that the ambivalence was normal and nothing to be ashamed of, they would feel less alone.

It now feels as if my role as a photographer goes beyond photography – for the first time I feel I’ve got a social mission.

Photography has many benefits but sometimes when working commercially it must be hard to marry what you are doing with yourself. But this is very worthwhile.

It is a really good feeling. I feel that I am using my voice in a really meaningful way, and that has been amazing.

Directed by Ruben Peeters & Sophie Ebrard

Talk us through how the exhibition worked – you’ve said it was multi-sensory.

The exhibition was a multi-sensory experience mixing pictures, moving image, sound and scent, exploring the essence of motherhood.

Alongside the self-portraits of my daughter and I was the scent of a newborn baby (that I created with a scent engineer); a birth room with the sound of a woman giving birth, pictures of my youngest daughter’s birth; and a diary entry that explained my ambivalence towards motherhood. It was an entire immersive experience. The exhibition was set in my own house, which added to the experience as it is the place where I am a mother.

Are those pictures supposed to be deliberately uncomfortable?

The pictures of my youngest daughter’s birth [which include one of the placenta] are meant to share something that is not commonly shown in photographs. These images were displayed in a cosy room; red coloured light enhanced the idea of the womb and the sound of a woman giving birth added to the intensity of the images.

Most of our contemporary ideas about childbirth come from risible depictions in Hollywood movies. A woman shouting and the doctor telling her to push. A moment later, we reveal a glowing mother holding a tiny newborn. This is not reality! By showing pictures of birth, I wanted to open the conversation and show the truth behind it: it’s brutal and raw, as birth is.

I have to say it was quite an intense room. Most people were quite taken aback after experiencing it.

So viewers go on a deliberate journey around the exhibition, just like you, which you can see from the video.

They do. And at the very end of the exhibition there was a journal, an ode, where I explained my journey to motherhood.

It’s a fantastic thing that you felt confident enough to have this honesty and for something really beautiful to come out of it.

Thanks. I feel that it’s a beautiful, honest journey. As an artist, I was compelled to tell my story and hopefully help other women along the way. I’m over the moon about how it was perceived by visitors.

Now the idea is to really spread the message. I hope I can reach a wider audience, first with this video, and then by getting the exhibition to tour in other countries.

For the work to grow in purpose and enable other women to feel stronger, less alone, is really admirable.

Thank you.

Let’s focus on another strand of parenting – breastfeeding at work. You’ve written freely about its complications, how it’s affected you on a job [getting fired], and have questioned the advertising industry’s true commitment to equality behind the scenes, away from the empowered voice women now have in advertising. It was based on personal experience. Can you expand?

When I had my son Jules I was also breastfeeding and taking him on jobs. Six years ago, I can tell you it was a challenge to take a baby on set. I mostly had to hide him and breastfeed between set ups. As a first-time mum I felt conflicting emotions. I didn’t feel empowered, but I still did it. When Louison was born, I thought surely things have changed. Especially in the wake of #freethenipple and #freethebid. It turns out it was slightly more complicated than this.

The story goes like this: I had won a job from a large advertising agency in London. An agency, in fact, that bleeds hashtag feminism in many pieces of its work. After winning the job and mentioning my daughter would be with me during the lunch break to feed, I was told it wouldn’t be possible and I lost the job. This made me feel insecure and unempowered rather than ready to take on a job. It made me angry, because like many working mothers, I am instantly judged, not by my work and awards and past successes, but the baby on my hip.

I don’t think I would have written this article if was just an isolated event. It happened many times during my breastfeeding journey.

And my story is not specific to breastfeeding. This issue is bigger than boobs. Whether you breastfeed, pump or formula feed, options for mothers returning to work are extremely limited. In a society that craves female representation, workplaces need to ask themselves if they are designed for the realities of motherhood.

We should normalise it. Half of the entire world’s population has been doing it for thousands of years. We need people – men and women – to recognise breastfeeding for what it is: a normal part of life.

Similarly to I Didn’t Want To Be a Mum, I didn’t really expect so many reactions. It was not about naming and shaming, but saying this shouldn’t exist. Now this article is out there, and the issue has been recognised; hopefully women won’t have to experience what I have been going through.

You’ve done a good job this year for women. 2019 has been your year!

You’re right. I guess I should be proud. Thanks for saying this.