Conversation with Jørn Tomter

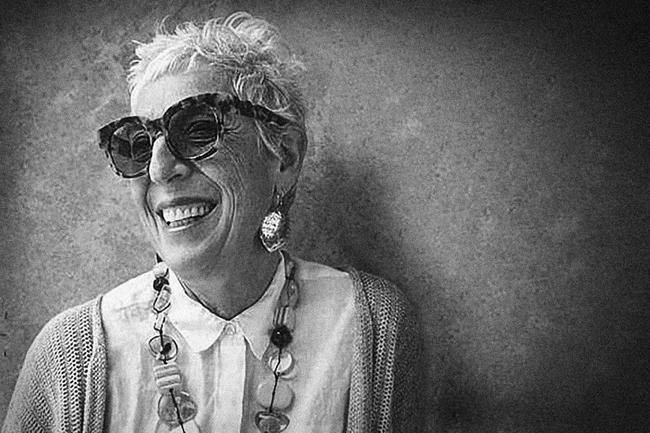

Jørn Tomter is a Norwegian photographer living in London. He loves to document people in communities and tell stories about their everyday lives, no matter how big or small. His current long term focus, I Love Chatsworth Road, is an intimate adventure of epic proportions about the place he calls home. What started as a simple photography project to record the rich history, heritage and rapid changes in his neighbourhood has evolved into something much more, with a regular print publication and website. It has become a way to bridge gaps and bring together the community.

Other social documentary projects include The Norwegian Way, about an annual youth festival in Norway, which created quite a stir when it was published a few years ago.

Jorn’s more commercial portraiture work has seen him shoot the likes of Paul Smith and Damien Hirst.

Jørn, sitting with you here it is quite obvious why your pictures are so genuine and open. You are so welcoming and great to chat to. And everybody around here knows you and loves you. But how did your journey begin? And why did you choose photography as your medium?

I have always used photography as a way of connecting with others. Photography is my ticket, my excuse to talk to someone, anyone. I was quite shy when I was young and the camera helped to get rid of that a little bit and helped me to talk to people.

I then eventually used the camera to see how others lived. It was one of the reasons why I wanted to do documentary photography. I used to look at all the amazing war documentaries or conflicts that are photographed, that are so important to document and create a record of. But I really loved taking pictures of everyday people around me. I knew there were things right here, on my doorstep, in Norway or England, that I could and would want to document. And that documentary photography doesn’t always need to be about horrible situations or about people who don’t have anything, who are on the edge of survival. I have always enjoyed photographing everyday people more than – let’s say – celebrities.

I came to London in 1997 to study at LCP, I think it’s LCC now. I thought it was exciting to come to London, everything was happening. It was different to Norway. And I was able to study courses that were not available in Norway at that time

It must have been so exciting to be in London and knowing that you were here to do documentary work. Are there are any photographers you admire?

I have always had a keen interest in August Sander’s style, Philip-Lorca diCorcia and Martin Parr from his earlier days. But the photographer who has always been with me is August Sander.

Oh, and Tony Ray-Jones too. He was the inspiration for Martin Parr, he made this really great book about England called A Day Off: an English Journal. It’s from 1974. It is great.

So that’s interesting. That work, and Martin Parr’s work has a certain sense of humour. But we love the empathy in your photographs. You see the light part of humanity, but you also have an incredible respect for the people in your pictures. Can you tell us more about why you decided to create I Love Chatsworth Road?

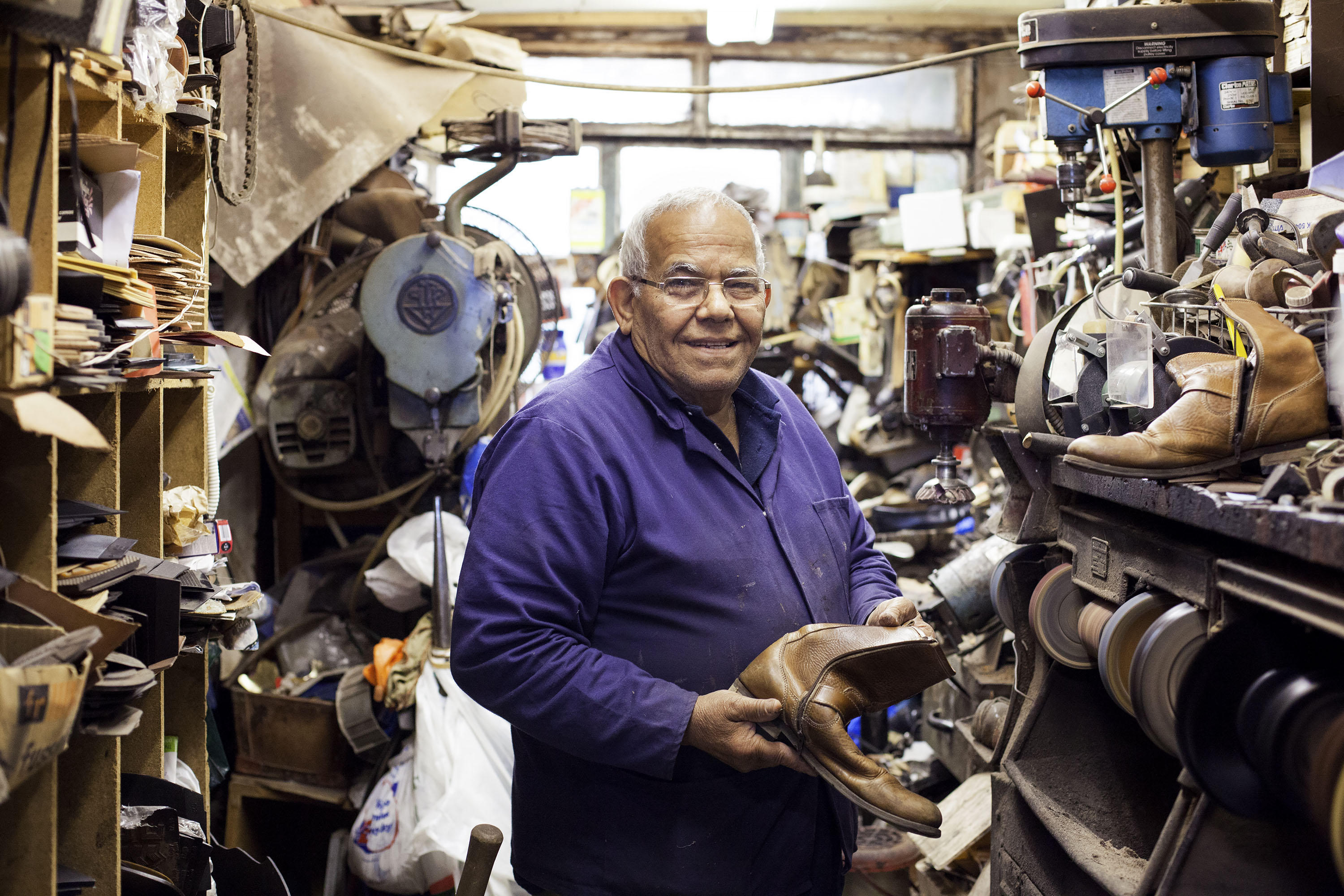

I find it so interesting to document people’s lives, some of my happiest moments are when I walk into a shop and start chatting to the owners. I always take a picture of them and hopefully it turns out well, then I often find out they have been there for something like 40 years.

Yeah, the area is really interesting in that way. So many buried stories. When did yours start?

This project really began when my wife and I bought our flat in 2007. I thought the street we had bought on was fantastic and needed to be photographed. We moved to Berlin at the time but I took pictures of all the shop fronts every six weeks; every time I came back to London. I knew the neighbourhood was going to transform quite a bit. Many of the shops were run by older people and they hadn’t really changed much since the 70s.

It was lucky for everyone that you began to document the shifts in the neighbourhood.

When we moved back to London, I started photographing the people more and more. I always had this dream of documenting a neighbourhood. But then I never followed through. I had always gone overseas to take pictures. When our first child was born and I didn’t want to travel as much any more it felt like it was a really good opportunity to document my neighbourhood; the one I lived in. I really wanted to create an archive of the area and then just see what happens.

You are not just documenting. You are also publishing. When did you decide to make the magazine?

Initially the magazine wasn’t the plan, but the streets became my studio. I had so many pictures that I thought I needed to get this out in print. That is kind of how the magazine started. There are always a few keen people who want to be photographed. But as more and more people started talking about what I was doing and realising it was free to them, many more wanted to be photographed.

That’s so great. It is inspiring to see that your project was so embraced by those in the photos. You clearly anticipated certain shifts in everything around you. Was it a part of the motivation for the project that you felt as East London became more gentrified that you wanted to document the change?

I wanted to capture the change because I knew it was going on, and that it was unstoppable. With the 2012 Olympics, lots of money was being put into East London. More and more people moved here from London Fields, Dalston, Shoreditch, as those places became too expensive and too arty. People wanted to come here and have a bigger house for less money. It felt like a good opportunity to document the changes and look at the different phases in four or five years.

I think many people don’t realise that a proper documentary project takes a while. It requires a lot of work, over a longer period of time; many people.

Yeah, I am very inspired by August Sander, for example, how he documented Germany in the 1920s and 30s. I think there are so many more people moving into this area, people like ourselves, I wanted document the people in a trendy coffee shop but also the chicken shop that has been here for 20 or 30 years.

That’s quite a challenging situation in some ways. You are here and you are documenting something, and you are also part of the change and the memory.

Do you think the area has been able to retain some of its heritage? What do those you photograph think about all this?

It’s a constant discussion; it always depends on who you ask. Lots of people say the old Hackney is gone, that it’s too expensive for people to buy here. Whereas other people say it’s better because their kids can run around and feel safer. However, there is still an interesting mix here if you look at the shops on the streets; but all of this may or may not last.

How do you see yourself in this context? Has your way of working changed? Has your view of the neighbourhood evolved as you have been working here?

You become a bit blind to the changes when you have been in an area for too long, it becomes harder to find the eccentric, interesting things. Now, I very often meet people and they put me in touch with someone I haven’t met before. I work much harder now to get into people’s homes and to see how they live; looking at the social housing part of the area, and what they do. There’s plenty of cool things happening there, they have quite a few events and I want to try and photograph them as well.

What do you think is your role as the photographer in the community? Do you think you have played a role in bringing people together?

I hope I have played a role. People say I have. I would love for those who have been here a long time to be friends with – or least try – and connect with people who have just moved in. If you grew up here you should be able to go into a coffee shop and buy a coffee even though you think you might not be welcome there. If you have just moved in here you should be able to go down to the estate and talk to people.

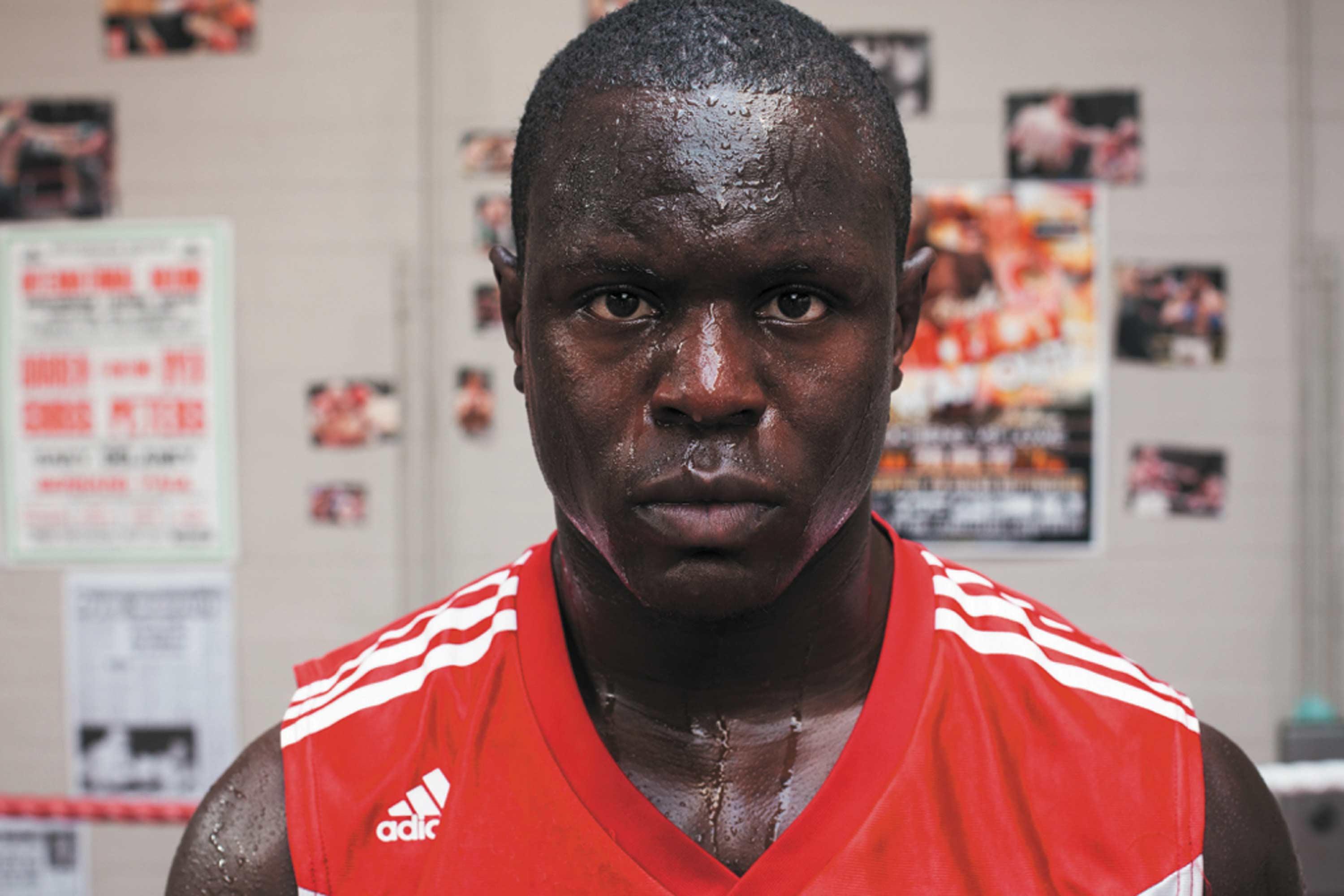

One example is a youth and boxing club called Pedro Youth Club. I have been taking lots of pictures there and been writing about them quite a bit. I made them a big story in one of the editions of I Love Chatsworth Road. I wanted to make people aware that this is one of the few places where young people can go and actually do something with their life rather than hang out in the streets. The guy who runs it said that about 12 years ago they had to close for a couple of years; and crime on the streets went up.

I hope to build some kind of bridge, I don’t think I am going to save anyone but it is a contribution and I would hate to make a magazine that only had white creative people in it. If it was that way I might as well just do commercial advertising jobs and not my own stuff; there has to be a reason to do what I do.

With your photography you are able to add importance to places and people who matter, even if they do not show up in agencies’ creative briefs. I like that you are able to amplify the community aspect of photography. Do you feel that photography as a medium is changing?

I think if I started aged 19 and today, I wouldn’t have been a photographer. When I started I really wanted to learn about the darkroom and developing, it all felt really exciting. Around 20 years, people thought it was really interesting that you were a photographer. You basically knew how to do a hand craft. But now everyone says they are a photographer. If I take a photograph of a middle aged man I know he is going to tell me that he has a better camera than me.

Yeah we have heard that too. There are even jokes about cameras. But we all know it is not the camera that takes the picture.

Everyone seems to be taking pictures but nothing is being kept. Nothing is being put into a system, and nothing is being categorised. People are just putting pictures on to their hard drives or on to Instagram and they never look at them again.

That is so true. But in the long run, projects like yours will prevail. You are shooting with a certain future in mind. So many camera operators out there, so few true documentary photographers.

So where do you feel photography is heading?

In a few years’ time so many people will realise that they have lost their pictures. Hard drives are going to be difficult to read, pictures will be lost in some kind of cloud system. Inaccessible.

But there is still a market to have a particular style as a photographer. If you want to survive as a photographer, you need to create something that everyone can’t necessarily copy straight away. The market for professional photographers is definitely getting smaller. It will be interesting to see when cameras can take certain pictures and everything will be sharp and in focus. Then you can decide in post-production where you want to put your depth of field and so on. Then there will be more editors and fewer people taking pictures, many more people making up stories. Now everyone can buy a really good automatic camera and take relatively good quality pictures. It used to be that you had to hire someone to take technically good pictures. That’s no longer really the case.

I see photography as something that many young people do now. But then as they get older there will be a small minority who will be able to stick to it and earn money with photography in the years to come. It is good to have a side project as a photographer to create some additional income, since the budgets out there are getting smaller.

It is something that we hear from a few photographers. The market is shrinking. More and more people take pictures, but not many of them create meaningful photography. And we also see more and more now that real photographers embrace some projects that are relevant to them personally. That’s something that will hopefully never stop.

Could you tell us a little bit about the Norwegian tradition, Russ, and your project The Norwegian Way?

We have a National Day in Norway on 17 May, the celebration of Russ, which dates back quite far to 1905. It happens all over Norway, about 95 per cent of all kids finishing school take part at that time of their life. The five per cent who don’t are the cool ones who are too cool or intellectual, and don’t like to take participate.

For the last 30 years or so the party has been going on for about three weeks until the National Day.

I came back to Norway in May a couple of years before I started this project. I saw all these young kids sitting by the waterfront drinking and watching the sunset. They were all wearing different colours. It looked like a graphically interesting picture. I thought I needed to photograph this. I did some research and found that no one had ever documented this celebration in Norway. I decided to give it a year or two and see what happened. I was rather keen to use the Norwegian landscape quite a bit, as I think it’s truly beautiful and interesting. So in many of my photos the kids just sit, look at the landscape and drink.

And this has been going on for more than 100 years?

Yes. Even Spring Break in America doesn’t include such a big proportion of students. I don’t think there is anything similar to it in the world. I thought I would document it so that people can see what happens and remember how wild the celebrations were.

So how does the Russ work?

Most of the kids buy a bus with their friends, or a van or car and then paint it. If you’re really cool and have lots of money, you install a sound system inside it; perhaps even a bar, some even have their individual branding or logos; it’s really thought through. Some of the kids spend hundreds and hundreds of pounds to make their bus the best. They get boiler suits and sweaters and jackets with their logo on the back and on the bus. They then drive around late at night and play really loud music and give each other dares to do which are recorded by adding another thing to their hat. On the last day, which was originally meant as a political rally, it is just parades. In the broad sense it is more about the kids themselves now, their personal experience. It has become more of a Norwegian rite of passage.

That’s pretty incredible. I think most people outside of Norway are not aware of this at all.

It takes a bit of time to understand, so I asked some of the kids to write a diary. It’s about their experiences, what they did. Some wrote that they don’t even like the celebrations. I felt it was important to include the text from their own point of view. After three years of taking pictures and only taking colour photos, I thought they looked a bit too nice. So I started looking at war photography from Vietnam and I started to mix it up with black and white film.

In the first year I hung out with the groups quite a lot, maybe for as much as two or three weeks. I had a Tomter photographer branded vehicle; one bus invited me to take a few trips with them up and down. I was 28 back then, the age gap was a bit big but not too big, but after the fifth year I thought I was a bit old. The loud music and people throwing beer at me was starting to get too much. It actually felt like being in a war zone sometimes.

Your work about the Russ was published as a book, The Norwegian Way, by Generation Yacht in 2007. It seems such an adventure for someone who is not Norwegian. Do you have any dream projects?

I think a dream project would be to travel the world and create similar work to I Love Chatsworth Road, but in very different neighbourhoods. If I could spend a year in Williamsburg and then do a year in Delhi, then maybe on a beach in Indonesia and then bring it all together, that would be great. I hope I will slowly build a brand around this kind of photography. I would like to be able to eventually pay contributors properly.

The important thing about photography is to keep doing what you really love and do it your personal way. If I didn’t do this, I might as well not be a photographer. For me, it is really important to have a personal project, and that is what keeps me going.

Can you give us a glimpse into the next edition of I Love Chatsworth Road?

I have been working on different thoughts. I would like to move away from a supplement and create a story or a path of pictures and then combine those with lots of stories, poems or experiences from people in the neighbourhood. I don’t want it to be a template and look the same every time but I also don’t want it to be too arty. For me, it’s really important that people learn a lot about the neighbourhood.

I hope that my photography becomes a positive way of documenting people and their lives. I want it to become a historical document that people will look back at over time.

Jørn thank you so much for this interview. We are looking forward to the projects ahead. And we will also keep our eyes open for neighbourhoods around the world.