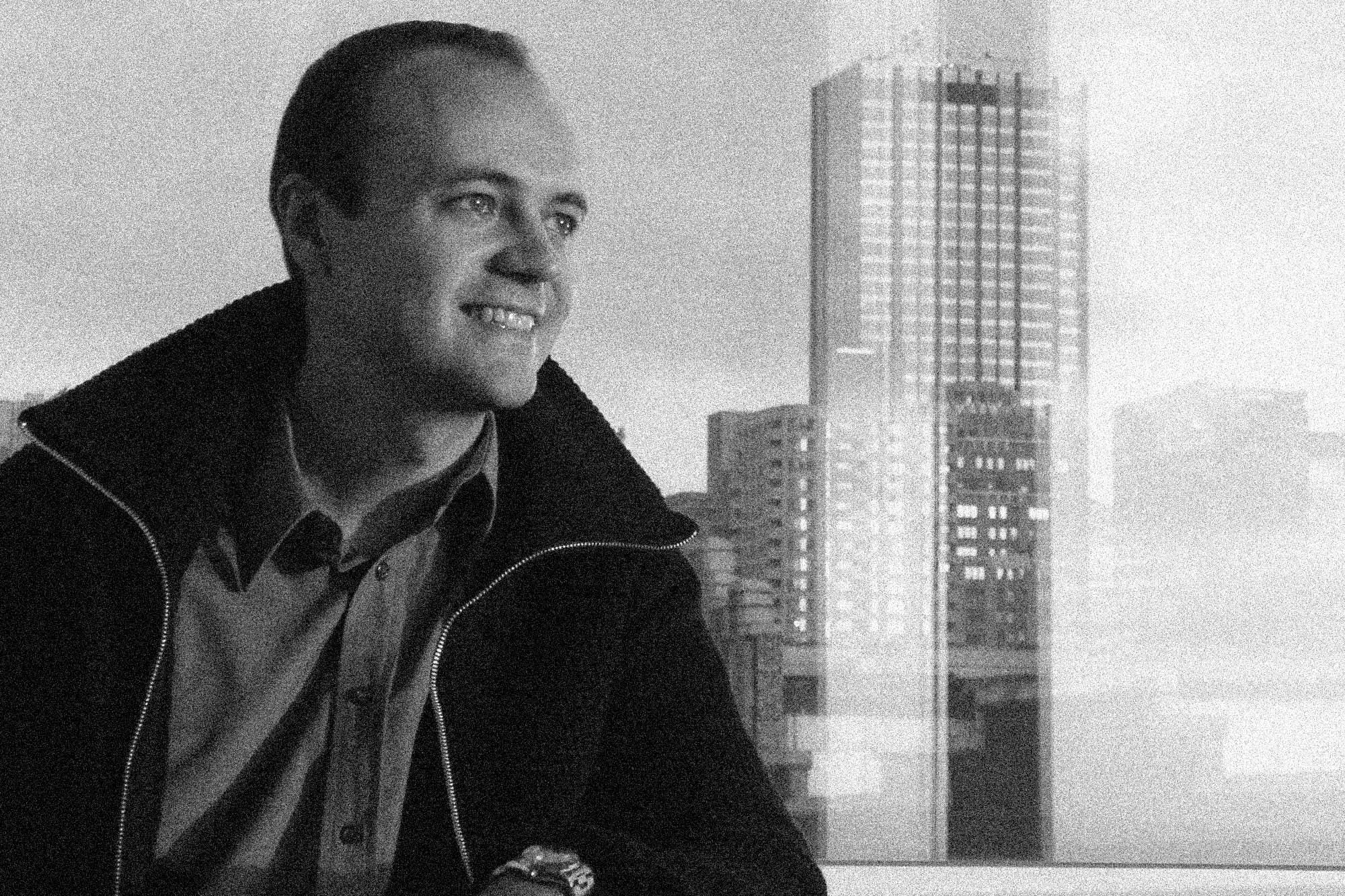

Artist and architect Jorge Otero-Pailos on rethinking culture and urban development

Artist, architect and historic preservationist Jorge Otero-Pailos is a fascinating guy to talk to and if you get the chance to see some of his installations in person, grab it, they look pretty mind-blowing. For now, we can at least share some insight on what excites and inspires him.

Jorge talks to us about the intersection of art, architecture and historic preservation. We also hear his views on urban development through preservation, and how the relationship between people and things – a thread that runs through his work - is so important in urban development and the future of our planet.

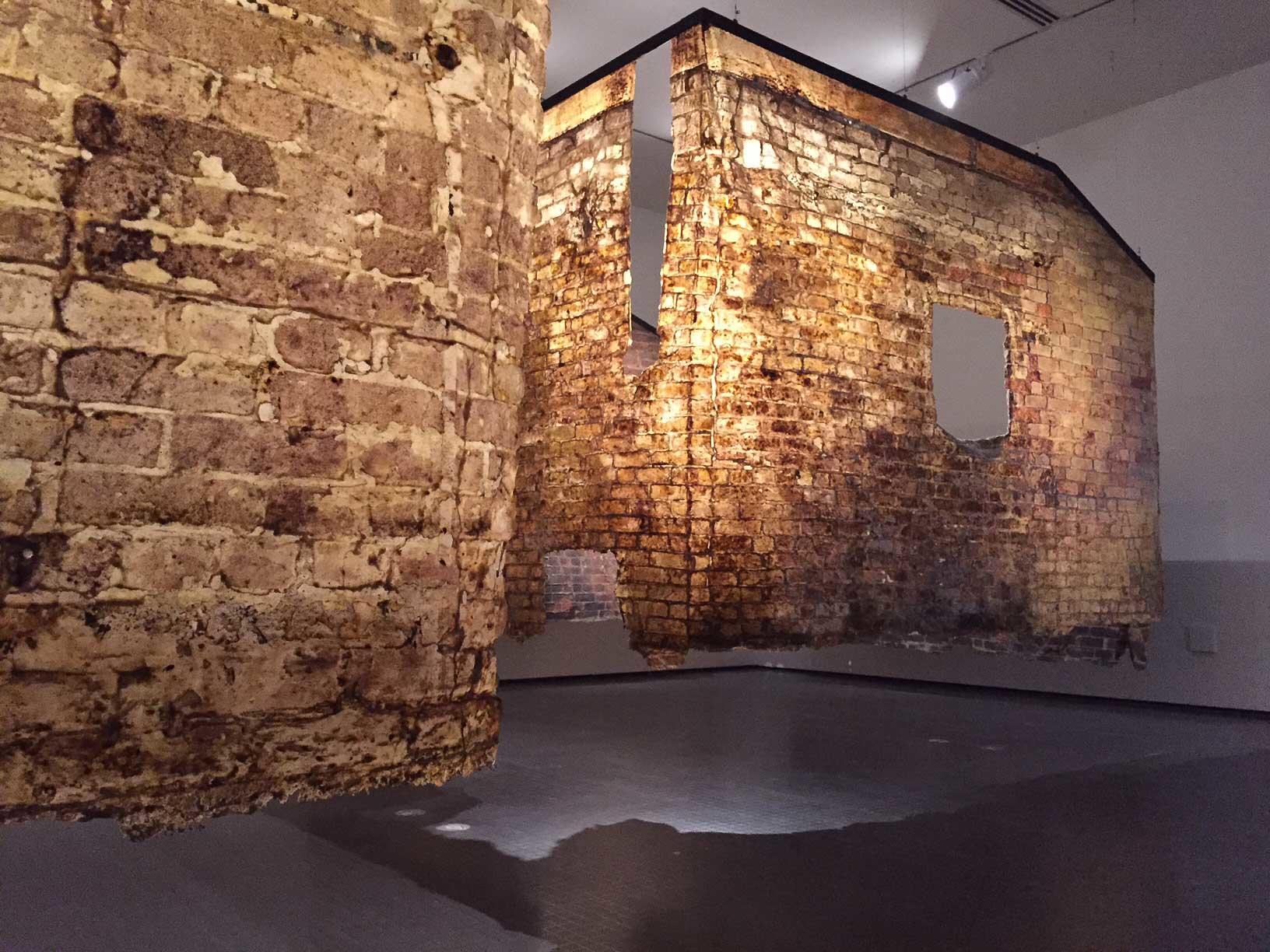

The Ethics of Dust: Doge's Palace

Jorge works at the intersection of art, architecture and preservation. His interest in the relationship between them stems from a passion for monuments or historic buildings – for “objects that exist in the public sphere and that we all share together”.

He feels that art, architecture and preservation are some of the most obvious ways we can talk about these objects.

Tracing these passions back, Jorge believes his early exposure to different parts of our cultures, and to the monuments that define them, ignited these interests. As a child in the ‘70s, he travelled around the world to see monuments because his mother worked for an airline.

“This was before mass tourism in the way we experience it today, so there were obviously fewer people at these sites. But there was already this question of “What are we looking at?” There were people there relating to these places in different ways.”

“It was the way I began to understand what Egypt was – by looking at the Mamluk architecture and the way people related to these water fountains around Cairo,” explains Jorge. “Or the way people prayed or entered temples in India and what you encountered there, which is so different to what you find in temples and churches in Europe.

“These objects were a way to see and observe how other people behaved towards them, and through them to discover other cultures. I think that was really important for me.”

And today, as an architect and artist, he believes you are really always thinking about culture and what it is.

The default position, says Jorge, has been the idea that you make something new that gets added to culture, “and that’s how you shape it: just by continuing to add things”.

“Over time, I became interested in the ways that things already circulating in culture were actually also instrumental in reshaping it. These objects could be recast in interesting ways, and as a way to rethink culture.”

So rather than adding an object, “which then dies or becomes out of use and a new one comes in, only relevant for an instant”, Jorge focuses on things that last as cultural objects for a very long time, which is why he was drawn to monuments.

The Ethics of Dust: Old United States Mint

(photo credit: Jorge Otero-Pailos)

For Jorge, his work is all about intervening in this space between people and things. But he is more concerned with larger social groups, with what we call culture, than individuals: how we transition from one phase of life, from one historical period to the next.

Nowhere is this more evident than in his ongoing, decade-long project The Ethics of Dust series, which takes latex casts of different historical buildings in cities and countries around the world. They might not sound very pretty but these installations really are beautiful. Liquid latex is applied to part of a monument and then peeled off, with its surface dust and pollution, which is then suspended within this glowing, translucent latex.

The series has so far included London’s Westminster Hall and Trajan’s Column at the city’s V&A Museum, the Old United States Mint in San Francisco, the U.S., and Doge’s Palace in Venice, Italy, to name a few.

Jorge sees this dust as a prolific cultural product, which many just view as pollution, plain and simple. But he is excited by it, and the layers of culture and meaning.

He sees it as this ‘in between’: it is partly us, partly the objects, he explains. “We cannot have all those monuments without making that pollution. So dust has its place, somehow, rather than just being something we want removed.”

On a very basic level, Jorge says The Ethics of Dust series takes care of these objects that have lasted so long. On another level, in taking care of them, you actually change them ever so slightly.

“After you care for something, that something is no longer the same, and it’s in that change that I’m very interested, because when objects change, what we can do with those things also changes,” he explains.

“And if culture is what we can do with things and each other, if our ability to do something with monuments changes, therefore our culture slightly changes.”

The Ethics of Dust: Alumix

(photo credit: Patrick Ciccone)

With The Ethics of Dust: Westminster Hall, the process involved a large team working together over six years to clean the building. All the dust that came off the walls (from 900 years of history) was eventually cast and exhibited inside the hall, which has had a central role in British history since the 11th century.

By pure coincidence, the show opened on the day of Brexit. “So all of a sudden this object that’s the origin of Western parliamentary democracy, there it was at a moment when the process of democracy had yielded this very unexpected result,” says Jorge.

“The fact that the building had changed ever so slightly at that moment (that it was now slightly cleaner), but the dust was still there…it was very moving. To be there at that time, with those thousand years of dust, really cast that moment, that cultural transformation and tremendous cultural shift, into a different light.”

Jorge’s whole The Ethics of Dust series is about “allowing us to see buildings that have been around a really long time in a slightly different way, to help us sort out the transformations in our cultures today”.

He feels they have an important role, enabling us to see the transformations in our cultures as part of a continuum, rather than as breaks.

“I think the default position is to see cultural change as radical breaks. For example, viewing the Industrial Revolution or fall of the Berlin Wall as pre-world and post-world order.

“But there are things that linger on from one world order into the next that actually make the new world order possible. So that is my interest in these monuments, and in cleaning them: helping us to frustrate the idea that all change is radical change.”

In a simple sense they are offering a history lesson from dirt and pollution. But it is also about buildings and monuments that linger on operating as contemporary art.

The Ethics of Dust: Westminster Hall

(photo credit: Marcus J Leith)

With Westminster Hall, says Jorge, it is a contemporary building, used for its purpose. “But it is also an object travelling through time, coming to us from a deep time we don’t understand very much about,” he adds. “And now here it is, shaping how we engage with each other; a fundamental part of contemporary life.

In that vein, Jorge feels we are seeing a very important transformation in what it means to be both an artist and architect in today’s world. He sees more and more artists now looking, as he does, at how “we can change the way we engage with what we already have, rather than just adding new stuff to the world”.

“It’s not about a world of Duchampian ready-mades and the changing context they are used. It’s not about taking a shovel and putting it in a museum.

“It’s about intervening very subtly in the space in between people and things, so that you actually change the relationship between people and things that are already around in the world.”

The objects around us obviously help us to make sense of our own culture. And Jorge is fascinated in the objects we choose to focus on – the monuments and museum objects. But also those things we don’t think should be part of culture, that we don’t view as cultural.

“Pollution is an emblematic example of something we feel defines culture negatively – we want to push it out precisely in order to have culture,” he explains.

“It also suggests that at a very basic level, culture has to do with cleanliness, with a purity of sorts – we’re washing out things that don’t belong. And that very idea is under a lot of pressure these days, because we are confronted with other views of what doesn’t belong.”

He adds: “Dust resides very much on top of these objects that we cherish as part of culture. But then at a certain point we remove that little surface, as if it didn’t belong.

“There is so much encapsulated in that act about what culture is: that its form of caring is to remove, to exclude the very thing that makes culture possible. You certainly couldn’t have had Western industrial culture without pollution. And it’s that paradox that fascinates me.”

The Ethics of Dust: Maison de Famille

Louis Vuitton (photo credit: Jorge Otero-Pailos)

For a very long time, we’ve been relying on curators and museums to tell us what objects we go to, to sort out what our culture is, says Jorge. “And now there is a type of suspicion of the curator, of the choice.

“So I think people are moving towards monuments, not because of who made the choice originally, but because of the meanings they’ve picked up along the way, that those meanings are not of one person, but of a group.

“People are more interested in that group process: how does that choice get made in a way that is not necessarily conscious, but still shared?

“The choice gets made in the way we relate to these objects over time, and the way we care for them, and our decision to care for them. We form attachments to these objects, as if they were vital parts of our existence.”

Jorge says his work is guided by the insights of psychoanalysis. Though this is a whole other topic for another day, he admits he’s been very influenced by British psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott and his views on the role of transitional objects, that essentially help children discover reality.

“We, as adults, are also still trying to sort out reality. We are often very focused on ourselves and our own problems. But what about what we ask of each other, how we ask things of each other, of others who we don’t necessarily share a home with?

“We never talk about the people we don’t have verbal exchanges with, and actually, that is what culture is. If you are part of a culture, you often don’t have a lot of exchanges with those people who are part of it. But you do come together around certain objects, and you ask things of each other around those objects. You have expectations of how we all behave towards monuments.”

Jorge focuses on those expectations of how we are supposed to behave towards that space. “So the works I create just sit in that space and force us to really begin to slightly change the way we relate to that space, as a way to open up a new way of thinking about a culture, open up a question.”

Many of us share these spaces, and relate to them, in cities, which is an important topic for Tea & Water. The future of our cities will ultimately affect our cultures. In the same way he now views his role as an artist, Jorge believes urban development through preservation has better cultural value than destruction and reinvention. Architecturally, he says we have to acknowledge that our world’s idea of urban development is one that was created to serve industrialisation and industrial technology.

“It is a very 19th idea: the notion that you remove the old and start afresh is one that serves industrial production,” says Jorge.

“We’ve done very, very well but now the world is built up. We’ve used up most of its non-renewable energy. And so the problem is different now because we have built in such a way that these buildings are now falling apart.”

Most of the world was built after the Second World War, and was meant to last 30 to 40 years and is now falling apart, explains Jorge. “In order to replace it, we would need to once again use all of the world resources, which we just don’t have.

Prize-winning preservation architecture:

Master plan for New Holland Island,

St Petersburg, a collaboration

between Jorge and Workac

“So we cannot physically, and in good conscience, say the answer is to tear it all down, put it in a heap and start over, because that is only feasible for the very, very wealthy who can pay for the energy.”

We need to think about a different relationship between people and things, says Jorge. “We need a new kind of culture that is able to take what’s there and change it ever so slightly, to make it relevant and useful.

“I think for urban development that is super important. And it means rethinking the way we practice. For mayors, it means rethinking how they collect taxes and how they create more tax revenue, because their thinking is that the way to create more revenue is to build more square footage.

“And for real estate developers, it means rethinking their business model: working out how to make profit off an existing building, with its inconsistences and complexities. That just requires a different business model.”

So really, Jorge believes if the people fundamental to urban development start to truly rethink their business models, there is no reason our planet can’t continue to develop and grow in a smart and sustainable way.

“If you look at the business model of urban development – it has been one of consolidation. It has all been about aggregating and consolidating in order to build efficiencies, which is a very dated (19th century) way of thinking: that the way you make profit is by standardising and consolidating.

“And that by consolidating, you are building efficiency, in the sense that less people can manage more because there are fewer inconsistencies between what needs to be managed.”

In Jorge’s view, today’s Internet, sharing economy and digital technology, mean we can relate to the world in a way that doesn’t necessarily require homogenisation and consolidation in the same way.

“That’s why I think there is a very important role to play for monuments, because they are unable to be consolidated,” he says. “Precisely their importance is that they are unlike other things, but have a very vital function in transforming culture.”

Jorge is also professor and director of historic preservation at Columbia University’s graduate school of architecture, planning and preservation in New York. He is founder and editor of the journal, Future Anterior, and his scholarly contributions are numerous, as are his awards from art, architecture and preservation organisations, including the UNESCO Eminent Professional award. He is also a member of the Academy of Arts and Sciences of Puerto Rico. His work has been commissioned by and exhibited at major museums, foundations and biennials, most recently the Chicago Architecture Biennial.