City spotlight on New York:

notes from a true Brooklynite

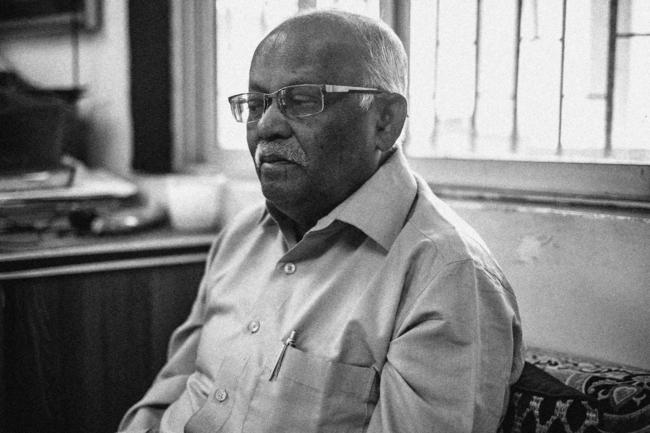

As part of our global cities spotlight, we are exploring New York. Here, third-generation Brooklynite Micheal McLaughlin shares some past and present perspectives on the area he knows so well. Micheal, a photographer, has lived most of his life in Brooklyn, moving just a few blocks each time over the past 40 years. We also talk to him about cultural creativity, transport and what growth and gentrification means for city life and sustainability.

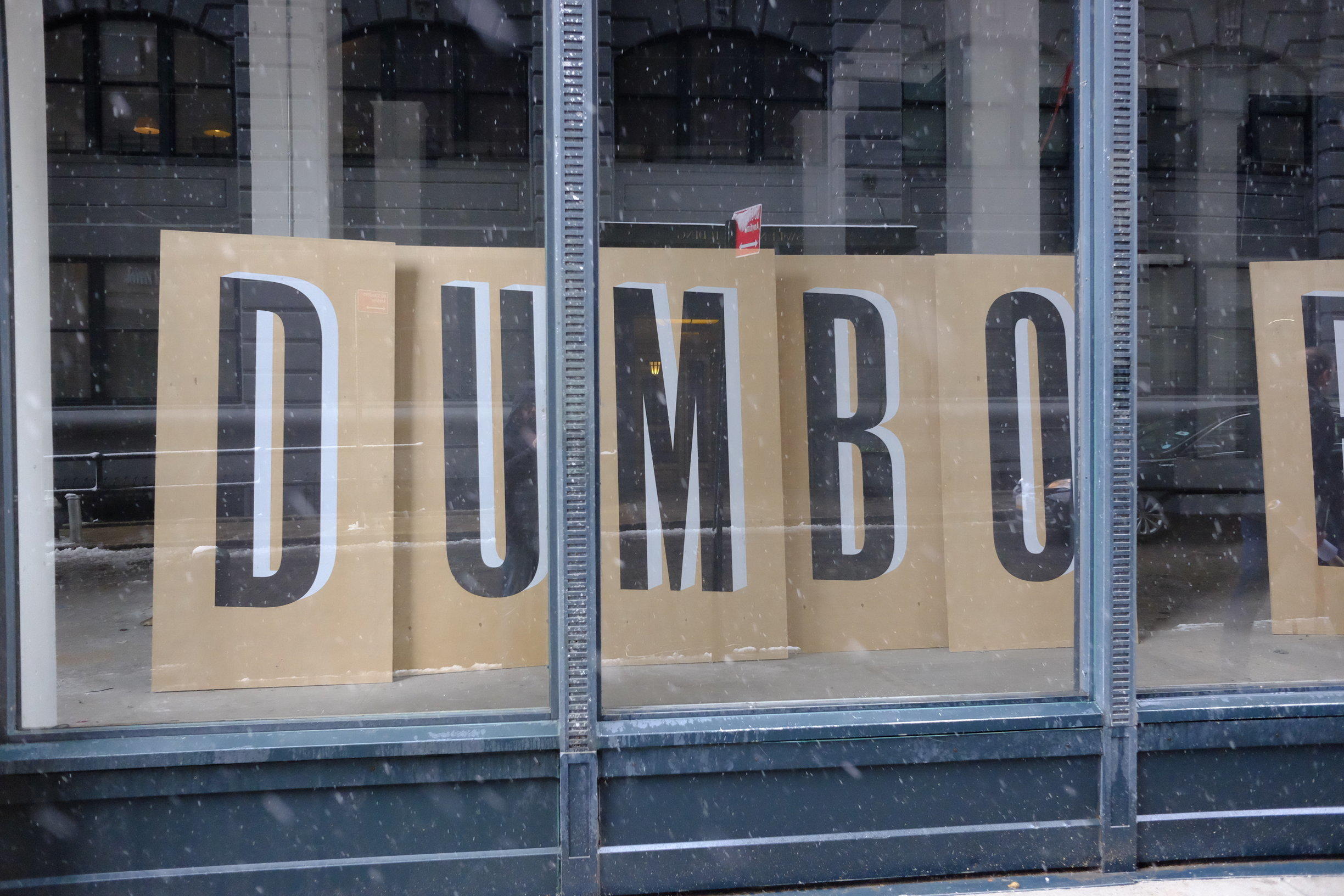

So many transformations have gone on in Brooklyn and especially in the neighbourhood of DUMBO. What’s the Brooklyn you remember from the old days?

When I was much younger, friends living in Manhattan used to make fun of me and my Brooklyn friends that we had to go back there at the end of the night, as it was not the cool place to be at that time. The area has become much more popular, for good reasons, but it’s definitely become a less sustainable kind of place in some senses. We live in a historic district but when you go outside it, the sky’s the limit, as far as zoning for development goes. Our local hospital is being turned into a 40-storey condo. But it’s across the road from an area where you can’t build up more than four storeys. Our public library is now being developed into a 30-40 floor condo building. I think there are about 30,000-40,000 more people here in this little neck of the woods who were not here a dozen years ago. So you can feel it in terms of congestion.

DUMBO is fantastic the way it has transformed. It didn’t exist 20 years ago. I used to go to a lot of parties down there when it was just an abandoned warehouse district of lost spaces. It was a different kind of place. And it could not have happened without one Brooklyn-based family [the Walentas family] being in control of most of the development. They came in and founded the real estate company Two Trees. If it was not for them, none of these great things would have happened. The sense I get is that they came with a vision and saw something in DUMBO other real estate developers hadn’t.

Everyone knows cities have a cultural side through the history of their buildings. But it’s refreshing to see real estate developers who place so much value on cultural creativity, which is really the beating soul of local communities.

Yes, if it had been a more cut-throat developer or someone only interested in pushing square footage, we wouldn’t have any of that. So it’s because of the Walentas family – the husband and wife [David and Jane] sat on that property for years until they could get the right zoning.

When St Ann’s church moved its performance arts centre down to DUMBO [shortly after 9/11], that made a real difference. It’s now St Ann’s Warehouse [based in an old spice-milling factory on Water Street] and is a real institution that’s been going since 1980. It used to be located on Montague Street, our high street in Brooklyn Heights. Performances and music gigs were going on all the time. When Lou Reed and John Cale first got back together they played here in Brooklyn Heights, at St Ann’s. And when Joe Strummer and The Mescaleros last played, they played down in DUMBO. The St Ann’s space shows the wonderful way the Walentas family has looked out for artists.

Even with things like the historic carousel down on the waterfront in DUMBO [the East River in Brooklyn Bridge Park], this was a pet project of Jane Walentas [the 1922 carousel was bought at auction in the 1980s and pain-stakingly restored over many years by Jane before being installed on the waterfront in 2011]. The transformation in this spot has been incredible. Back when my son was born just over a decade ago, before Jane’s Carousel was put up and before the civil war building was repurposed, we used to go down to the waterfront with all his little friends and run around when there was a lawn there and nothing else. It’s amazing how fast it’s changed, just in the span of my son’s life. There are always good arts programmes going on there. It’s a pretty wonderful place.

The gentrification of DUMBO and other parts of Brooklyn echoes many other city neighbourhoods across the world. But what do you feel sets DUMBO apart from other parts of Brooklyn in this respect?

I think it’s a unique neighbourhood because of a singular vision that has attempted to include residential, commercial and artist spaces in one neighbourhood. One of the interesting things about DUMBO is that because this one family owned nearly all of it, and has run it like a benevolent dictatorship, it doesn’t have the kind of anything goes development that’s happened in Williamsburg, for example [another Brooklyn neighbourhood]. I have tons of friends who were in Williamsburg back in the 1980s and early 90s who had 5000-square-foot loft spaces, way before anyone moved there. But most of these industrial spaces have now been transformed and in between them these tall ‘finger’ buildings have been built – 24 feet wide, running up nine storeys.

Williamsburg is a very popular area. But one of bad things about it is that there is only one train going in and out. And the tunnel there is about to be shut so it’s the last place in NYC I think I’d want to be living right now. Just in terms of everyday movement, it’s a tough place to get in and out of. People have spent a fortune to buy properties over there and there’s only one subway. Down in DUMBO there’s only one subway stop but it’s only one stop away from everything else. So it’s very accessible.

Let’s talk more about property.

Just like in London and other cities, there are insane real estate prices and there’s not really any give to it. We live in a neighbourhood [in Brooklyn Heights] where there is no inventory when people are even looking for places. We managed to move into another place this past year but if we were just starting out [on the property ladder] there is no way we could afford to live here.

If you think of sustainability in terms of people and retaining cultural diversity, then this rich cross section of people all cities have diminishes as neighbourhoods technically flourish economically.

Neighbourhoods do need all types of people – teachers, artists, cops and firemen can’t live in these parts any more, so that’s the downside of development, as I’m sure it is in many cities.

The spread of gentrification pushes young people, professionals and old-time locals further and further out. How do you combat that and keep a sense of diversity in communities?

It’s all market driven. The cost of housing is absolutely the most punishing factor of change in New York City. Affordable housing as a percentage of new developments has to become the norm.

Brooklyn Heights is a wonderful family neighbourhood, with little through-traffic and accessible to seven or eight subway lines. My son walks back and forth to school. It’s still a pretty stable population, largely because the housing stock is primarily co-op apartments [which you’re not allowed to let out] and rentals. It’s a bit less transient overall. But it’s all changing. It used to be that a lot of people were artists and real new Yorkers and that, of course, has been changing over the past 12 to 15 years. We lived in one building full of artists, lawyers and Wall Streeters – it was a real mix. You had people 90 years old and two years old, all in one building. Our current building is similar to that but you’re finding less and less of it.

Those are the kind of things I still love about this neighbourhood and New York in general. Brooklyn Heights is really a pedestrian area and you run into the same folk on the streets all the time in this particular neighbourhood. In other places in the city people don’t stick around that much.

Let’s talk about transport and traffic. One big project being planned is the BQX light rail (Brooklyn Queens Connector).

Traffic is a major issue here and the subways are at the breaking point. Congestion pricing needs to be implemented. So I’m not sure the light rail is the most logical of transport solutions. It’s also in a flood zone (in Red Hook and near the [Brooklyn] Navy Yard) and would go right through downtown Brooklyn, which you want to avoid at all costs whether in a car or other road transport. It’s going to be interesting to see how it’s pulled off and how often it runs.

I know there’s a light rail in Portland, another U.S. city, which works pretty well. Conversely, the one in Washington apparently had plans for four lines and cost way more than it was supposed to and has now been cut down to just one line.

Portland is a great example. Its light rail is fantastic and been there for over 30 years. And it works. It is the right size city for light rail, it came at the right time and it was certainly part of Portland’s development as a more popular city. Here in New York, there are so many other issues that need to be dealt with that it’s not as much of a priority. The light rail will be nice if it gets done. But there are other issues, like the BQE highway [Brooklyn-Queens Expressway]. Parts of it are 35 to 40 years beyond their replacement date already, so there is probably going to be some kind of catastrophic failure of one of these bridges or highway sections at some point. You’ve got around 150,000 vehicles running on the BQE each day.

The light rail would go right by the Navy Yard and also open up Williamsburg, but travelling into downtown Brooklyn and past Red Hook would be a more difficult passage to make.

Here, the subway really is the lifeblood of the city. That is the main priority for New York. It’s actually amazing to think how many millions of people use it each day. And it’s so much better than when I was a kid, even though it needs vast improvement now.

Overall, how do you feel about all the transformations and development you’ve seen in your city?

New York, in particular, is at a crucial point of change now. How do we make it a liveable city for regular people? Like London and other global cities, most people will live in a neighbourhood for a while, then after their first kid they question whether they should move out to the suburbs or a more affordable area. A second child is usually the breaking point. To have three bedrooms in most Brooklyn neighbourhoods, for example, is nearly impossible these days.

I’ve never seen the stakes be so high here in New York, as far as cost and disparity go. It was always a place when I was younger where you didn’t worry about money or having a place to live or parking your car. New York is the flip side of that now. It’s certainly not the city it was, but that is no surprise.

Patti Smith might not be moving here now. The Ramones would still be living at their mum’s houses! It’s just a different kind of place. And I’m sure the same thing has happened with London and other places. Almost all of my friends who were here 20 years ago are out in LA or elsewhere now. They come back for openings or visits but most people left because NYC became too expensive, and they needed more studio space. It feels like there are fewer and fewer of the types of people left that New York has been known for. The legend of New York, of punk rock, abstract expressionism, people living in lofts, that’s just become further and further from reality.

So the challenge now has become about how do you still get the city to work on a day to day basis? How can you have a place where teachers can afford to live and send their kids to the schools they teach at? And firefighters can still live in the city where they do their jobs. Once it becomes this homogenised type of place, not only do services start to suffer but the city itself becomes less interesting.

A lot of my friends and family used to be reporters for the New York Post and The New York Times. There is a writer called Paul Schwartzman, who now writes for The Washington Post and grew up on the Upper West Side of New York in the 1970s. He said recently how New York is the only city you can miss while still standing in the middle of it.

If you live here long enough, just like any city, you walk around and see so much that has disappeared. But there are still so many very wonderful things about New York. And as new people come in they are seeing it for the first time. For all those people who lived here years ago, it’s a different deal. But even going around the city with my 11-year-old son, I just love the way he is so excited about how things have changed. Kids kind of point out how much better the city is than it used to be.

So whatever happens, you’ll always have the fresh perspective of children. Ok, everything is more expensive, life is faster and more competitive. But if you are seeing stuff for the first time, you obviously don’t stand in the middle of what’s gone, thinking of what you don’t have in the present and what you won’t have in the future. It’s a very different hat on.

I have observed that with friends who are here for the first time or visiting with young kids, and that’s opened up my eyes to other points of view, which is reassuring. Children allow you to see how things rejuvenate. These are the people who are going to hopefully make these cities better places in future and they are learning very different things than we did as kids.

Photo credits: Micheal McLaughlin