Social sustainability: putting the heart into urban planning

In our Cities series, we have already talked about thinking beyond the smart city, about urbanisation and the changing face of our landscape, and how crucial urban areas are to curbing our carbon footprint. Here, we talk to Dr Cathy Baldwin, a social scientist offering some blue-sky thinking. She believes it is absolutely vital for city policy makers, planners and designers to understand how to create urban infrastructure that helps communities behave and think in ways that will make them stronger and better able to cope when affected by climate change.

You’d think people would be front and centre of any urban planning, given that humans are the beating heart of their cities. But Dr Cathy Baldwin says the social dimension of sustainability and urban resilience is currently sorely neglected. The hardware of cities tends to be prioritised by governments, she says.

And while robust physical structures are obviously vital, social relationships make a big difference in how urban communities thrive in daily life and cope in times of environmental crisis.

Cathy, who is affiliated to the University of Oxford and Oxford Brookes University, believes that with the pressures of rapid urbanisation, economic growth and climate change ramping up in cities around the world, something needs to change – and that shift is to socially-aware planning. This is what she and Robin King, of the World Resources Institute’s Ross Center for Sustainable Cities, are trying to shout from the rooftops about.

In a joint report on what they feel is a global problem, but also a global opportunity, they talk about built environments that promote social interaction, where people properly connect to one another – through neighbourhood networks or collaboration on group initiatives. If social and community cohesion is strong, people’s health and well-being, and daily quality of life should improve. It can also make residents better able to collectively pull together to deal with, and adapt to, natural disasters.

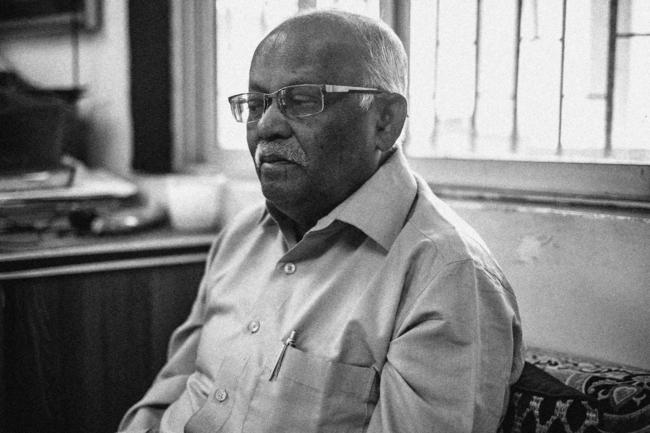

Pic credit: Kate Lamb/VOA

“What I’m talking about is people’s everyday behaviours and their welfare,” says Cathy, whose training is in the behavioural dynamics of communities and seeing how they work. “It’s all very well making statements about this and recognising it, but what’s anyone doing about it?”

And that’s where their report, What about the people? The socially sustainable, resilient community and urban development, comes in. They have compiled a list of behavioural norms and states of mind based on positive real-life examples of daily life and conditions of crisis around the world, and come up with practical recommendations that can be tapped into for future builds. So the report is aimed squarely at those drawing up sustainable or resilient city development plans – policy makers, planners and designers.

“This needs to be addressed formally within cities around the world,” explains Cathy. “There is a unique opportunity needed right now, everywhere, to incorporate this sort of social/behavioural dimension, which affects bottom up community behaviour, states of mind and ultimately group level action.”

Cathy says she has spent years looking at city resilience and sustainability strategies, and reading UN reports and high level sustainability reports.

“People talk about strengthening the physical structure – the actual hardware of the city, so that it’s robust and can take shocks and knocks and last for a long time. And then there’s making the economy sustainable, and also protecting the world’s natural resources.

“But what about protecting the social well-being and social life of people in their communities going about their daily lives and interacting together in a way that’s healthy? It’s about operating in a cohesive, conflict-free and positive social environment that’s actually good for people’s health and well-being. There are massive social connections between people’s networks and how cohesive their communities are.

“And that plays a lot into the idea of collective action,” she adds. “If there are social problems in a community, say flooding or intermittent earthquakes, having this strong collective ability for people to get together and help each other out – on an emotional level (in terms of providing support) and then on a practical level, is so important to a community and city’s resilience.”

This stuff is so important, says Cathy, and she just doesn’t see that kind of soft behavioural dimension in any of those high level documents.

Photo credit: Micheal McLaughlin

Their report offers a global perspective and evidence from 12 countries across all continents, on how certain built environments help to foster behaviours, thoughts and feelings that benefit communities. These include feeling connected and emotionally attached to your neighbourhood and community. It also explores the effects of such behaviours on community resilience, looking at three types of urban structure used by masses of people in a public context every day: housing, transport hubs and public spaces. Though the report didn’t consider commercial or heritage infrastructure, its recommendations are just as vital for other built environments where people are regularly present, says Cathy, whether it’s a new financial district, concert hall or redeveloped city waterfront.

There is evidence from all these crisis situations around the world, says Cathy, whether it’s slum or city flooding, heatwaves, hurricanes or cyclones, that what makes the “key difference” to a community coping during and after one of these crises, or building up their ability to cope better in future, in daily times, is not the physical structure of your home. “It’s how good your networks are and how cohesive the relationships in your community.”

“Communities are made up of individual people, but together those people can achieve things at a greater level – it’s those everyday networks, and everyday states of mind that propel someone into action,” she adds.

So from the moment urban planners and designers first talk about creating a unique public space, Cathy says they need to be asking themselves: What behaviours do we want to see? How will this grow the social capacity of a community? “It feels like a lot of architects think in terms of wanting to see people enjoy themselves and experience a space as part of their quality of life,” says Cathy. “They have good intentions, but they are not getting down to the nitty-gritty of the longer term outcomes of a place.”

“Building for sustainability and resilience is really important and these guys are looking long term at the physical aspects. But we want them to incorporate the elements we recommend [in our report] into their design process so they can have intentional impacts on a community that are positive in terms of social and wellbeing.

“It’s about designing with positive social goals, rather than dealing with any negative incidental impacts after a space has been built.”

“It’s about designing with positive social goals”

Cathy realises the intangible aspect of behavioural and psychological impacts and outcomes is “really scary for people who have a more conventional attitude to urban planning or engineering”.

“But these people need to start talking to social scientists like me,” she adds. “Among architects, there are still a lot of assumptions people make and take for granted about what the planned impact of a design will be.

“People don’t necessarily do their pre-construction research with potential tenants, residents or users from an area, or track social outcomes in the long term, says Cathy. “That should be an essential part of management of any urban development.

“It doesn’t even need to be expensive high level academic research – it’s about working with properly qualified social science practitioners to make the links between the hard structure, the cost and economic profit implications, and the social impacts and longer term outcomes. Most of the time talking to people is free.”

For their report, Cathy and Robin searched around the world for urban development projects where there was behavioural data showing there had been some kind of intentional thinking going into building/redeveloping or involving the community in managing them.

One great example is in the U.S. city of Portland, Oregon, where the community was involved in restoring three neighbourhood squares to create a ‘sense of place’ – where people feel part of the place they live, have a sense of security and emotional connection. New features include community-designed street murals, information kiosks with bulletin boards and hanging gardens. Before and after psychologist surveys of local residents found improved mental health, sense of community, community capacity and social networks.

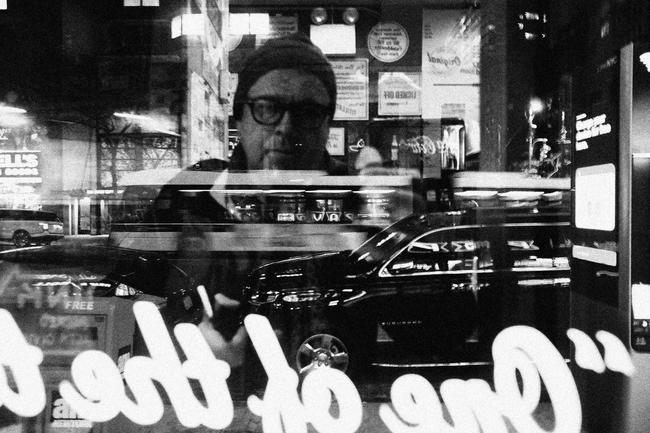

Photo credit Louise Thornley

A glowing case study on the disaster resilience side looked at earthquakes in Christchurch, New Zealand, focusing on three residential communities with public spaces or areas that promoted social interaction and connection. These locals also had a culture of volunteering and being proactive before the quakes. All this helped them feel invested in their community and many were motivated to join official consultations on how to rebuild and restore it because they cared.

Their pre-existing neighbourhood organisations also came together to help with relief efforts, which included putting furniture and art in alternative spaces when the usual public spots were damaged.

The city’s indigenous Maori community was also explored, which already had organised networks and cultural centres and a pre-existing culture of friendliness.

“They have very strong cultural values of being hospitable and looking after people, regardless of social, ethnic or faith backgrounds,” says Cathy. “They were quite incredible in the aftermath of earthquakes, opening their doors to everyone.”

Communities that fared the worst were ones with weaker social networks, and bad relationships with the local authorities, with whom they felt overlooked and powerless in ordinary times. This wider mistrust affected people’s willingness to take part in official consultations to rebuild and restore. Other factors such as poverty obviously play a role – as people don’t have as much time to help out.

So in neighbourhoods with a lot of diversity (the norm for so many of our cities globally today), where it is culturally celebrated, lots of different ways of thinking and doing things is considered a community strength. In those places, social cohesion nudges the community into a much more successful response to a crisis, compared to places with more tension and conflict.

Photo credit: Noah Sheldon

The report is framed in very positive terms – sharing case studies that show what can be achieved. “We realise we are spreading the good news and showing the best case scenarios, and not every project will unfurl with the same results,” says Cathy. “But we are trying to put this on the map, give it a voice and show the gold standard – of what you should be aiming at.

“This is blue-sky thinking and we know that in developing countries and less well-resourced places with poorer communities, sometimes even getting a community voice in a policy or planning process is a massive challenge, as it may not be prioritised or is politically difficult at a regulatory or legal level.”

Very few countries probably have the perfect governmental and legal infrastructure to implement exactly what we’re saying, says Cathy. “But you’ve got to start somewhere”.

We’ve all got a responsibility to create more liveable habitats, to make cities more resilient. If those in charge of urban development are missing a trick, they’re missing a vital chance to improve people’s health and well-being and make our cities more climate proof. And it looks like this report is exactly the opportunity they need.

Communities can have serious collective power: and those that feel a sense of social inclusion, safety, happiness, responsibility and pride are more likely to care enough to come together in everyday life and in times of disaster. And that is one vital way of protecting our people, and our planet.

Dr Cathy Baldwin also works with Ben Cave Associates, an independent public health consultancy.

Header image by Micheal McLaughlin

Noah Sheldon + Micheal McLaughlin are represented by

Tea & Water Pictures

All other photos by Witold Riedel